Student Discovers and Repairs Collection of Books at the College Library

What started as a summer job at the O'Malley Library has turned into a career calling for Tim Gress ’19 whose discovery of a book collection prompted him to learn about book restoration and pursue a graduate degree in library science.

You wouldn’t think that spending a summer cleaning out dusty periodicals in an underlit room in the bowels of the O’Malley Library would spark one’s interest in learning an uncommon, book-restoration craft, or even spark any ideas of what a future career path could look like — but it did for Tim Gress ’19.

When Gress signed on to help the library staff tackle the disorderly stacks in what pretty much is the library’s basement, he didn’t know what he’d find down there, hiding under overgrown piles of publications and concealed in the darker corners of the room.

What he found can be described as both a call to duty and a new ambition.

Chapter 1: Down in the Depths

“I started with everyone else, just putting books back on the shelf,” Gress says about his initial work in the library. “During the summer, we emptied out the whole bottom of the library — moving 100,000 books. I noticed that a lot of the books were broken and needed repair — they were rotting and falling apart.”

“I started with everyone else, just putting books back on the shelf,” Gress says about his initial work in the library. “During the summer, we emptied out the whole bottom of the library — moving 100,000 books. I noticed that a lot of the books were broken and needed repair — they were rotting and falling apart.”

So Gress, who is majoring in philosophy and religious studies, learned how to fix them. He watched tutorials online and consulted long-time library assistant, Joyce Gormally. From there, he began to build momentum.

“I learned a couple of basic things, and then I learned a lot on my own — reading things, watching things, and obviously doing it,” he explains. “I developed some shorthand that makes it quicker and easier.”

Gress then discovered that many of the books in the DeCoursey Fales Collection, which includes the complete works of many famous authors published from 1715 to 1966, were just sitting on a shelf and mixed in with the library’s main collection — and even available for checking out of the library. He had to take action. Thus, began another project, and more precisely, a new mission.

“This stuff was just sitting out there,” he says.

He went to the library director, William Walters, and expressed an interest in researching these books, the results of which confirmed that they were, indeed, quite valuable, as some were even signed by the authors.

“Tim noticed that the Fales books were in need of physical repair, and that the collection was being under-utilized in its old location in the main book stacks,” Walters says. “Then he worked with Susanne Markgren (assistant director of the library for technical services) and me to determine where those books ought to be shelved, to specify the kinds of repair that would be undertaken, and to determine how they could be best presented to our patrons.”

Gress had to do some sleuthing around the library to find all of the items in the Fales Collection.

“We knew generally where they were, but we didn’t know exactly where each one was,” he says. “I was looking through old stuff. There were some old memos, so I went to the shelves and checked them out, and I found them all and put them back together.”

Gress then set out to inventory every single book. He found which books were missing, which weren’t exactly missing, and assessed what condition they were in. There are more than 3,000 books in the Fales Collection alone, and 1,000 of them needed some sort of repair.

Chapter 2: The Repair Process

Many of these old books need repairs to their hinges, and some even need new spines, which makes sense after centuries of being opened and closed. Gress demonstrates the hinge-repairing process using several tools of the trade: folded-over paper, cardstock, book cloth, a bone tool, special book glue and hinge tape, and some common wax paper.

Many of these old books need repairs to their hinges, and some even need new spines, which makes sense after centuries of being opened and closed. Gress demonstrates the hinge-repairing process using several tools of the trade: folded-over paper, cardstock, book cloth, a bone tool, special book glue and hinge tape, and some common wax paper.

The work is precise, and it’s quite easy to confuse the steps. After all the repairs are made, the book needs to dry overnight before making its way back to its shelf.

Making a new spine, he jokes, looks like a science experiment gone wrong.

“You cut that off, and you can stick the spine back onto the cardboard when it’s dry,” he explains. “You put it in warm water, and after a couple hours, the cardboard peels off the cloth, and then you just glue it back on the book when it dries.”

Gress picks up an old electric stylus, as well, which draws all of those white numbers on the books’ spines. He takes white contact tape, writes on the tape, and it bleeds through onto the book, giving it that hand-written look that is not quite penned or penciled in — a sort of pre-cursor to labels.

“It’s kind of like writing with a pencil, but not really because it moves,” he explains. “I’ll just write the call number, the title of the book, and then the author.”

If the repairer is not very meticulous with mending, the spine could easily look like Band-Aid job rather than a new binding meant to keep the integrity of the original book jacket.

“There are horror stories,” Gress says. “Some people took Scotch tape. Some of them took duct tape. People have used medical tape.”

Gress sees it all, as he not only works on the special collections but also on the library’s main collection.

“My main job is the repair,” he says. “Not just the special collection, but the regular circulating books, too, because a lot of them get beaten up. They go through a lot, especially the ones that people take out for English class.”

Chapter 3: Back to the Books

The Fales Collection is a literary feast to behold. There are first editions by James Fenimore Cooper, Samuel Johnson, Washington Irving and Agatha Christie, just to name a few. There are remarkable details, such as illustrations from wood carvings, and beautiful leather covers. One can gaze upon the signature of T.S. Eliot. There is a first issue of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped from 1886 that even has a giant treasure map that pulls out of the book. The oldest item is a satirical analysis of Virgil’s Aeneid from 1715.

The Fales Collection is a literary feast to behold. There are first editions by James Fenimore Cooper, Samuel Johnson, Washington Irving and Agatha Christie, just to name a few. There are remarkable details, such as illustrations from wood carvings, and beautiful leather covers. One can gaze upon the signature of T.S. Eliot. There is a first issue of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped from 1886 that even has a giant treasure map that pulls out of the book. The oldest item is a satirical analysis of Virgil’s Aeneid from 1715.

Fales was a lawyer, banker, collector, bibliophile and yachtsman. His collection of books and manuscripts included approximately 50,000 items pertaining to various British and American authors spanning the 18th and 20th centuries. Prior to his death in 1966, he donated the bulk of his collections to New York University, the New York Public Library, the Morgan Library and Manhattan College.

“The majority of his collection — and presumably the most valuable and rare items — were donated to NYU,” Markgren says. “Unlike Manhattan College, they have the facility and the personnel to maintain a large special collection. However, we can appreciate, house, and deem special our own items in our own way, and by doing so, hopefully generate interest in and respect for the importance of libraries in providing access to information (old and new).”

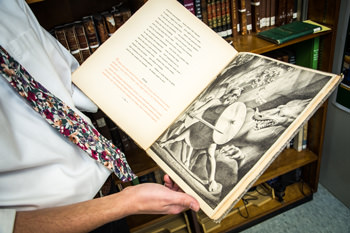

Gress goes over the books swiftly and with the same wonder that an English lit major or devoted collector might display for the collection.

“So, this is Sir Walter Scott … this is the letter addressed to Charles Dickens … this is Samuel L. Johnson’s dictionary [A Dictionary of the English Language]. It was printed in 1756. Just be careful with the cover. Washington Irving wrote a whole thing on Christopher Columbus; it’s this like four-volume biography on Christopher Columbus. That’s 1828. These are all first editions, first printing,” he says and gestures toward.

Gress can point out all kinds of interesting tidbits, and clearly enjoys showing people around the collections, as well as the library as a whole.

“Do you know Rockwell Kent?” Gress asks, while holding an edition of Beowulf. “He’s an artist, so he illustrated this book. Really cool. Instead of signing it with a signature, he put his thumbprint on it.”

Chapter 4: Bringing the Books to Light

After deciding to take them out of circulation, the library staff set about dedicating a room to these books, room 206, which also serves as a computer lab.

After deciding to take them out of circulation, the library staff set about dedicating a room to these books, room 206, which also serves as a computer lab.

“This room was one of the original reading rooms in the Cardinal Hayes Library,” Markgren says. “It seemed fitting to fill this room with old books and bring it to life again.”

The library hosted a special reception in February to debut the collections in their new space.

The Fales Collection basically fills up the back wall of the room, and the Dante and Sir Thomas More Collections take up several shelves on the other side. The Dante Collection consists of more than 400 titles, including Dante’s complete works and works about his life, and date back to 1802. The More Collection is comprised of 150 titles and close to 200 volumes chronicling his life, works and times. There’s also a collection of Encyclopedia Britannica, ninth and eleventh editions (the first modern English-language encyclopedia), which was formerly housed in the Chancellors Room.

With more than 4,000 books on display, what’s the oldest? Jack Sheppard by William Ainsworth, 1839. It’s basically the starting point for all the books in the room. The earlier publications are up in an office, for an extra measure of security. But members of the Manhattan community and visiting scholars are welcome to read them within the library.

Epilogue: The Next Chapter

Gress started working in the library as a freshman. He had been looking for an on-campus job, when his father suggested the library. The Huntington, Long Island-native thought it was a good idea, and shortly after, started working in the O’Malley Library about four hours a week. Now he’s there every day. It’s practically a full-time job, but it’s a labor of love.

Gress started working in the library as a freshman. He had been looking for an on-campus job, when his father suggested the library. The Huntington, Long Island-native thought it was a good idea, and shortly after, started working in the O’Malley Library about four hours a week. Now he’s there every day. It’s practically a full-time job, but it’s a labor of love.

“Now it’s what I want to do for the rest of my life,” he says. “I want to become a librarian and do the graduate library science program because you can get a special degree in library book conservation, which is what I’m doing.”

His work preserving and protecting the College’s old books has changed more than just his career outlook.

“It’s changed my life outlook, really,” he explains. “I didn’t even know this was a thing. I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I stumbled upon this after realizing the things that people overlooked over the years. I wanted to do something about it."

And with the support of the library staff, he accomplished just that.