Visiting Professor of English Explores Contemporary Craft Industry Through Creative Nonfiction

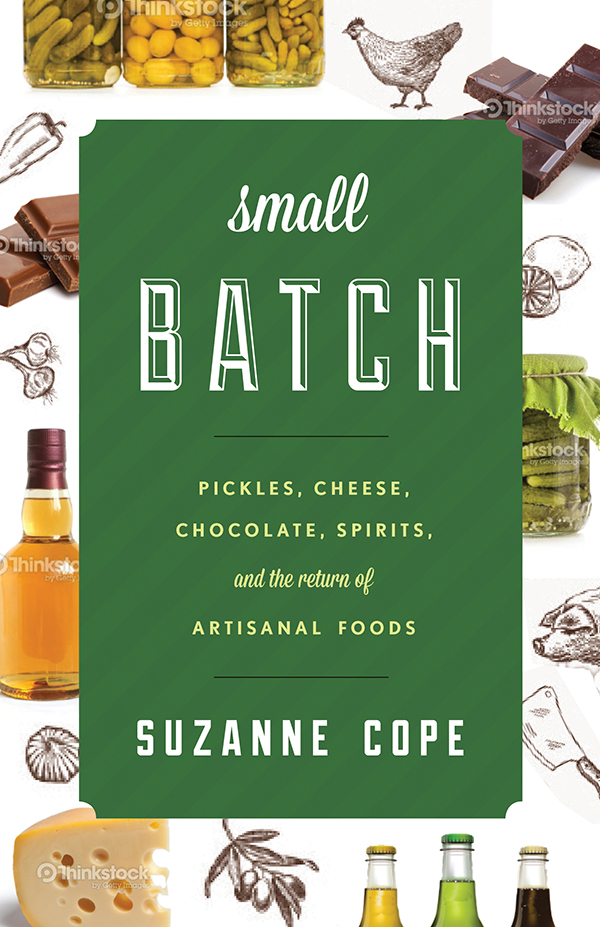

Suzanne Cope, Ph.D., published a new book “Small Batch: Pickles, Cheese, Chocolate, Spirits and the Return of Artisanal Food”

Literature: What is it good for? Absolutely everything, as proven by Manhattan College professor Suzanne Cope, Ph.D., who recently released a new book Small Batch: Pickles, Cheese, Chocolate, Spirits and the Return of Artisanal Food (Rowman & Littlefield, 2014).

Literature: What is it good for? Absolutely everything, as proven by Manhattan College professor Suzanne Cope, Ph.D., who recently released a new book Small Batch: Pickles, Cheese, Chocolate, Spirits and the Return of Artisanal Food (Rowman & Littlefield, 2014).

“Studying literature is a great way to learn creative problem solving, and it gives you the ability to connect the dots in your brain and think about any subject expansively,” she says.

Cope should know. The literature and creative writing professor (who also logged seven years as a publishing marketer) became an expert in the field of food studies after joining the Association to the Study of Food and Society (ASFS) on a whim. It’s where she met her eventual editor, Ken Albala, who encouraged her to expand her independent food research using methodology similar to those she adopted for her doctoral thesis.

A longtime supporter of the locavore movement (a locavore is a person interested in eating food that is locally produced and not moved long distances to market), Cope explored the art of producing small batch recipes in her own home, from canning fruits and vegetables to making cheese. After finishing her Ph.D. in Adult Learning, she found herself writing extensively on the subject and suspected there was a deeper story behind the longtime traditions that were quickly becoming popular trends.

Small Batch traces today’s evolving craft industry all the way back to early American settlers, and weaves together the stories of more than 50 artisanal producers of pickles, cheese, chocolate and alcoholic spirits.

Cope, a Brooklyn resident, was already familiar with New York City’s artisans, having witnessed the artisanal movement firsthand since moving from Massachusetts in 2012, but she still encountered some surprises along the way.

When she started the project, Cope associated the modern craft movement with the process-focused countercultural and anachronistic movement of the 1970s. But instead of communes, she found skilled craftspeople with entrepreneurial knowhow and a decided interest in flavor.

“What makes this modern artisanal movement different from the past is that instead of [individuals] trying to work outside the system in communes or other non-commercial ventures, we have people who are doing things within our current culture,” Cope says. “They want to monetize their business to be able to make a living. They also want to make a difference in an environmental way that impacts other people and not just themselves.”

During a recent interview, Cope reflected on her experiences as a locavore and a writer:

What does it mean to be a ‘locavore’?

I’ve come to embrace — in fact this is one of two of my future book projects — defining locavorism in a new way. I initially thought about locavorism as being literally what it was: consuming only food that’s produced within 100 or 500 miles, but I’ve come to think of it more as a philosophy of just knowing where your food is coming from and it adhering to your value system.

I am a member of the Park Slope Food Co-op and that was something that was really important when I moved, just to find a place where I can find these ingredients. I have a little garden, I am a member of a community garden and on the NYC compost counsel. It actually gave me a way to meet all these likeminded people.

What is your writing process like?

It’s different for different things. Someone told me once in my MFA program that the process of writing every book is completely different — I totally understand that now.

In Small Batch, there was so much research. I had a rough idea of how it was going to be organized, and how I was going to connect these people’s stories, but there were moments when wasn’t sure I was ever going to finish it!

But there are other pieces that just seem to be so organic. One day I walked to my community garden to pick a bunch of carrots that I had planted. I walked home with a handful of carrots and the essay came out of me immediately afterward. So, I’ve had those moments too, but much less often. Often it’s just slogging through.

Now that I have even less time to write, I mean, I’m busy with so many different projects and I have [a young family] it’s kind of like — the busier you get, the better you are at just sitting, if you have two hours or 45 minutes, you can just sit down and just make something happen. I used to say ‘I’ll just wait for inspiration to come to me because I have all day.’ I don’t have all day anymore.

What’s your perspective on creative nonfiction?

So many people think about fiction and poetry and drama as being the major literary dramas, but creative nonfiction uses all of the same tools, but it reflects on and tells real people’s stories.

I’m always on this quest to get creative nonfiction on that list of the genres that are taught in the literary canon — it’s just as important and just as interesting.”

Food is such a great universal way to get people thinking about their own experiences. I mean, find a person who can’t relate a food they ate to an experience they had or a connection to their past! I just love the integration of food and memory and writing and literature and I think that it’s sometimes overlooked in many places. That’s my quest, to bring that more to the forefront.

Read more at Locavore in the City, check out her recent New York Times essay, “Don’t Expect Dinner,” and plan your visit to Cope's pop-up event at Jimmy's No. 43 on Nov. 5.